What is Structured Literacy?

The goal of Kentucky’s Senate Bill (SB) 9 (2022), the Read to Succeed Act, is to ensure "all children learn to read well before exiting grade three (3) and that all middle and high school students have the skills necessary to read complex materials in specific core subjects and comprehend and constructively apply the information," (KRS 158.791(1)). The Kentucky Department of Education (KDE) is required to support “local school districts in the identification of professional development activities, including teaching strategies to help teachers in each subject area to: 1. Implement evidence-based reading, intervention, and instructional strategies that emphasize phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, comprehension, and connections between reading and writing acquisition, and motivation to read to address the diverse needs of students,” (KRS 158.791(2)(c)).

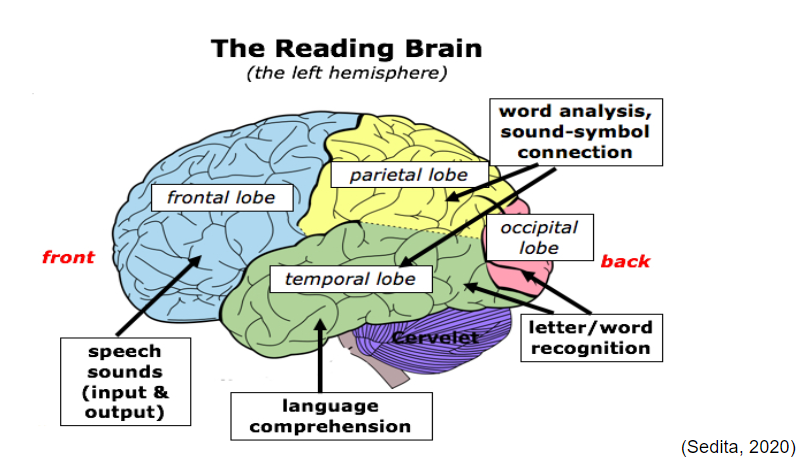

When understanding how the brain learns to read, educators implement Structured Literacy (SL) practices to ensure that all students are supported in becoming skilled readers.

Structured Literacy Defined

Structured literacy (SL) is an approach that emphasizes highly explicit and systematic teaching of all essential components of literacy. These components include foundational skills (e.g., decoding, spelling) and higher-level literacy skills (e.g., reading comprehension, written expression). SL also emphasizes oral language abilities essential to literacy development, including phonemic awareness, sensitivity to speech sounds in oral language, and the ability to manipulate those sounds (Spear-Swerling, 2019). SL prepares students to decode words explicitly and systematically. This approach not only helps students with dyslexia but there is substantial evidence that it is effective for all readers (IDA, 2021).

Learning to read is a complex process. Scientific research collected over the past four decades reveals what happens in the brain to enable skillful reading. Reading is not hard-wired in the brain. The neuropathways must be developed through explicit, systematic instructional experiences (Lexia, 2022).

People who become experienced readers use and integrate several regions of their brain, primarily in the left hemisphere including (Cunningham & Rose; Eden; Hudson et al., 2016):

The parietal-temporal region (towards the back) which does the job of breaking a written word into its sounds (i.e., word analysis, sounding out words).

The occipital-temporal region (at the back) where the brain stores the appearance and meaning of words (i.e., letter-word recognition, automaticity, and language comprehension). This is critical for automatic, fluent reading so that a reader can quickly identify words without having to sound each one out.

The frontal region (at the front) which allows a person to speak (i.e., processing speech sounds as we listen and speak).

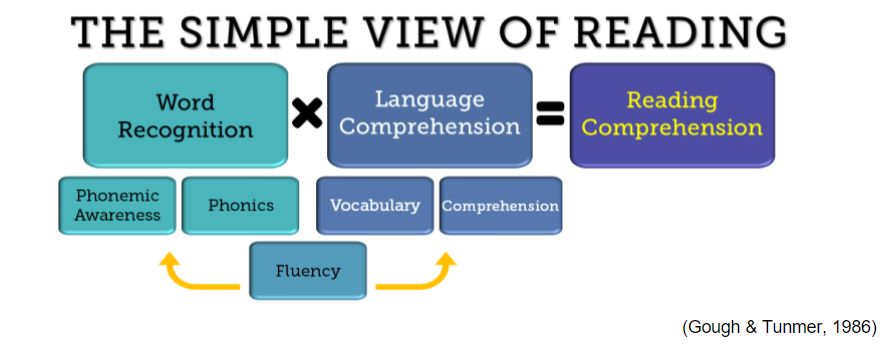

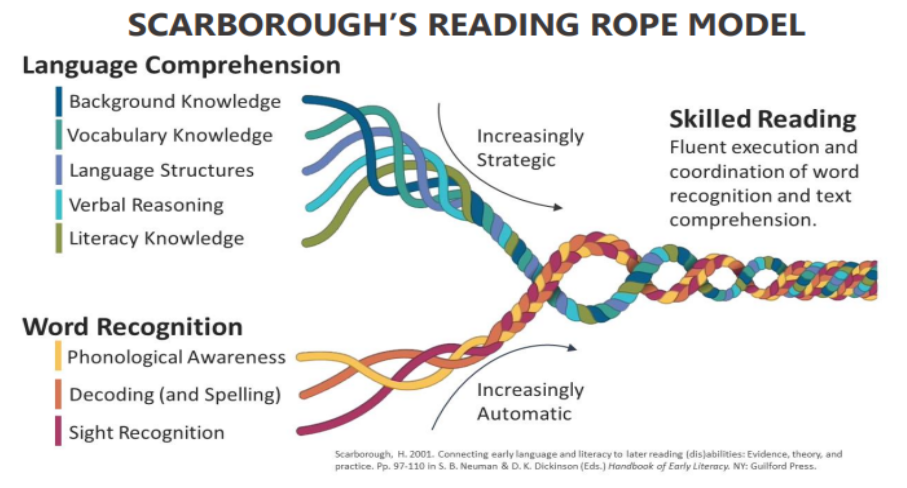

Despite common misconceptions, SL is not just about phonics; it includes much more. The Simple View of Reading (Gough & Tunmer, 1986) and Scarborough’s Rope Model (Scarborough, 2001) serve as frameworks for understanding and identifying SL.

The Simple View of Reading

The Simple View of Reading is a theoretical framework proposed by Gough and Tunmer (1986) that simplifies the complex process of reading into two essential components: Decoding (word recognition) and language comprehension (background knowledge, vocabulary). According to this model, reading comprehension is the product of an individual’s ability to decode and comprehend. The Simple View of Reading suggests that reading comprehension is improved by strengthening both word recognition and language comprehension. This framework allows educators to identify and address specific areas of difficulty in students' reading development, aiming to produce students who can proficiently read.

Scarborough’s Reading Rope

The “Reading Rope” model developed by Hollis Scarborough (2001) provides a comprehensive view of the multiple components involved in reading. It highlights the interconnectedness of various skills and processes required for proficient reading. The model emphasizes the importance of both word recognition (phonological awareness and phonics) and language comprehension (vocabulary, background knowledge, and verbal reasoning) as essential strands of the “rope” that contribute to reading proficiency. Scarborough’s model helps educators and researchers understand the complexity of reading development and guides effective instructional approaches to support students’ literacy skills.

Structured Literacy Is

SL practices are explicit and systematic in nature. Concepts are taught using direct instruction and modeled when necessary. The elements of language are taught sequentially with intensive practice and continual feedback. Reading instruction using the SL approach should be cumulative, that is, lessons build on previous knowledge, moving from simple to more complex concepts. Frequent assessments and progress monitoring are used to inform instruction and corrective feedback is provided. During each lesson, meaningful interactions with language must occur and students are given multiple opportunities to practice tasks. Lesson engagement is crucial during teacher-led instruction and independent practices are monitored. Lastly, a supportive learning environment where student effort is encouraged allows students to gain the self-confidence and motivation needed to gain mastery of skills.

Structured Literacy is Not

Instruction that is not aligned with SL does not place emphasis on phonemic awareness, decoding and spelling, even for beginning readers. There is no systematic grapheme-phoneme level approach for initial instruction and emphasis may be placed on larger units, such as word families, before students are ready (IDA, 2019). In early grades, children generally read predictable or leveled texts, which often contain many words that children cannot decode and tend to encourage guessing based on pictures or sentence context rather than facilitating application of previously learned phonetic patterns in decodable texts. Leveled or predictable texts are common in some interventions, even for poor readers (Clay, 1994; Fountas & Pinnell, 2009). Instructional time spent in direct teacher-student interaction may be limited, leaving children to work in cooperative groupings or independently instead of engaging in direct instruction from the teacher (IDA, 2019). When children read texts, even with a teacher, inaccuracies in decoding may be overlooked in the belief that errors are unimportant if they do not change the meaning (reading horse for pony). However, inaccurate reading prevents students from building fluency and often causes an overreliance on pictures. Relying on context does not work well for more advanced texts and can become a difficult habit to break (Floorman et al., 2016).

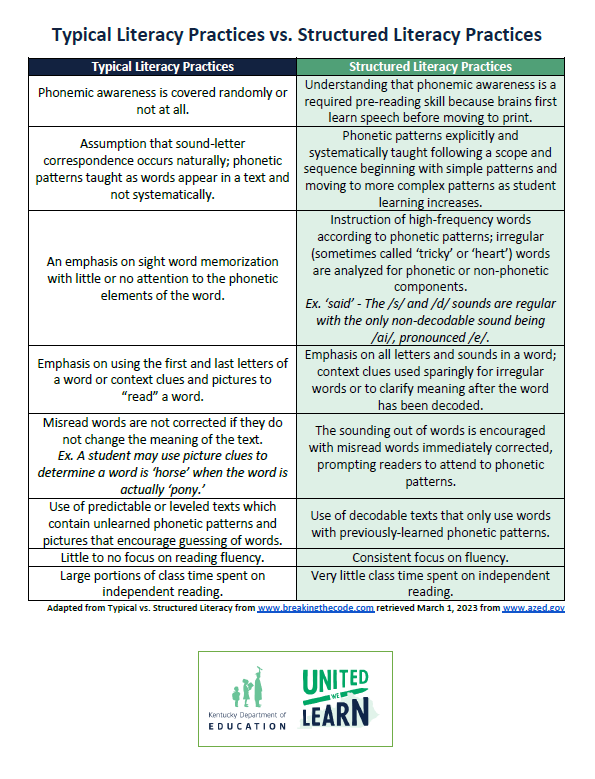

This chart shows the differences between typical literacy practices and structured literacy practices.

The Essential Components of Universal Tier 1 Reading Instruction

In its seminal report, the National Reading Panel (2000), concluded that comprehensive reading programs should include five

essential components. The five components, which are integrated into the most effective approaches for teaching reading to both proficient and struggling readers, are:

Word Recognition

- Phonemic awareness: The ability to distinguish, produce, remember and manipulate spoken words' individual sounds (phonemes).

- Phonics: Knowledge of the predictable correspondences between phonemes and graphemes (the letters or letter combinations representing phonemes) and correspondences between larger blocks of letters and syllables or meaningful word parts (morphemes).

Language Comprehension

- Reading fluency: The ability to read text with sufficient speed and accuracy to support comprehension.

- Vocabulary: Knowledge of the individual word meanings in a text and the concepts that those words convey.

- Reading comprehension: The complex process of understanding and making sense of written text through decoding, background knowledge and verbal reasoning, all of which are utilized by good readers to understand, remember and communicate what has been read (Montgomery et al., 2013).

Fluency, vocabulary and comprehension should emphasize

knowledge-building and access for ALL to

complex grade-level text.

How does Structured Literacy Support Universal Tier 1 Reading Instruction?

The

Kentucky Academic Standards for Reading & Writing work with SL to ensure vibrant student experiences in literacy. SL is particularly beneficial for all students in universal Tier 1 instruction, which refers to the general education classroom where most students receive their grade-level reading instruction. Through SL instruction, emphasis is placed on systematic and explicit instruction in phonics and phonemic awareness. Additionally, SL uses modeling and guided practice for each skill or strategy taught in tandem with vocabulary development to build background knowledge. Further, reading fluency and comprehension instruction are integral parts of SL that provide students with a strong foundation in decoding, phonics, and vocabulary (Foorman et al., 2016).

Substantial evidence (ESSA Level I) supports student instruction in phonemic awareness, decoding and phonics for developing awareness of segmenting sounds in speech and the ability to decode words and analyze word parts (Foorman et al., 2016). SL instruction prepares students to engage in higher-level reading tasks, such as understanding and analyzing texts, making inferences, and synthesizing information (Foorman, et al., 2016) (ESSA Levels I and II). By implementing SL practices in Tier 1 instruction, schools can ensure that all students receive comprehensive and effective literacy instruction. This approach benefits struggling readers by addressing their specific needs, and it also supports the overall literacy development of all students, preparing them for success in reading and beyond (Cunningham & Rose, 2013; Lexia, 2022; NRP, 2000; Montgomery et al., 2013).

How does Structured Literacy Support Reading Interventions in Grades 4-9?

Understanding that some students may need individual literacy support beyond grades K-3, the importance of reading interventions in grades four and beyond must be considered. The 2019 National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) reported that over a third of fourth-grade students and a quarter of eighth-grade students read at a level below NAEP Basic. Low reading scores in these grade levels are particularly troublesome when considering that so much of the curriculum in grades 4–9 (and beyond) requires the ability to read and understand increasingly complex texts. To understand the content taught in subject-area classes, students need to engage with and gain information from complex texts (Vaughn et al., 2022).

Recent research has demonstrated success in improving the reading level of students in grades 4–9 with reading difficulties. Reading interventions include both supplemental programs provided in addition to regular classroom literacy instruction as part of a multi-tiered system of support (MTSS). Through a five-year longitudinal study, literacy researchers have identified four recommendations for providing students in grades 4-9 with effective reading interventions. These recommendations and implications for teacher use can be found at

Educator’s Practice Guide for Providing Reading Interventions for Students in Grades 4-9 (Vaughn et al., 2022).

For more information about KyMTSS, please visit

KyMTSS.org.

References

Structured Literacy Webpage References

Questions?

Please reach out to Ashley Hill, Assistant Director of Early Literacy, at ashley.hill@education.ky.gov with any questions.